The Eco-Worrier on the History of Bicycles: Part Two

- eastlintontoollibrary

- Jan 18, 2021

- 5 min read

The role of the bicycle has changed repeatedly since its earliest years. There is no doubt that the first penny farthings and velocipedes were expensive and likely to have been the preserve of wealthy young men-about-town who no doubt also had access to horses or, if it was raining, hansom-cabs or even carriages. In contrast, the first part of this history ended in the late 19th century with the mass-production of the bicycle we recognise today; a steel tubular frame, equal-sized wheels with pneumatic tyres with the rear one driven by pedals through a chain. This standardisation resulted in dramatically lower prices. For most of its life the bicycle was therefore a practical, affordable means of transport, typically a faster means of getting to work than walking, especially for those not on a tram or (omni)bus-route. It was also used for leisure, but that role was principally to allow the rider to meet up with friends and to travel to local places of entertainment. The cycle-ride was the means to an end rather than a leisure activity itself.

In the post-war years millions aspired to motorcycles, scooters and cars, causing the bicycle industry in the developed world to almost disappear. It was a dramatic swing to the leisure market which saved the day; the Raleigh ‘Chopper’ for youngsters in the 1960s and 70s rescued the company.

Image 1: The Raleigh 'Chopper'

A decade later it was the development of the leisure ‘Mountain Bike’ or MTB in California which was a major factor in the resurrection of the entire industry. Just as a time-traveller from the 18th century to the modern day would surely be stunned at the very idea of the horsebox - (what - for transporting a means of transport?) - anyone from the early 20th century would no doubt be startled at the sight of a modern car carrying one or more bicycles on its roof or on a rear-mounted rack.

However, today’s experiences of traffic congestion, vehicle pollution and climate change have combined with a growing awareness of health to bring the bicycle back to the forefront of commuting. A growing awareness of the fundamental need for exercise has combined with the Covid-driven dawning that being packed in close proximity to others in a rush-hour bus or train is not a particularly healthy environment. Cities around the world are today being urgently reconfigured to make walking and cycling the preferred methods of travel for the able-bodied.

It is largely the incremental improvements in every aspect of its engineering during the intervening 130 years that have produced the sophisticated bicycle we see today. Perhaps the most important of these advances involved gearing which is just as important to those pedalling to work as it is to cyclists out for fun. Once the bicycle’s basic design had been settled there was always the option of varying the size of the front and rear sprockets to suit the local landscape. Flat countries such as the Netherlands could cope with a single high-speed ratio, but hilly regions demanded a lower ratio which did help the cyclist to cope with inclines but the downside was that travelling anywhere at speed demanded frantic pedalling. The problem remained that any significant uphill slope required the rider to get off and push.

The seriousness of this challenge is shown in the 750 applications to London’s Patent Office between the invention of the Rover safety-bike in the 1870s and 1906 for bicycle gearing systems. Despite these various British efforts, it was the “Derailleur” system invented in France in 1895 by Jean Louberre which swept the board. It was doubly-timely because the freewheel mechanism was developed at almost the same time, allowing cyclists to ‘coast’ downhill without constant pedalling. Louberre’s mechanism involved a series of successively smaller sprockets, today known as the ‘cassette’ attached to the hub of the rear wheel and a lever-mechanism for the rider to move the chain progressively from one ‘cog’ to the next as conditions required. The official bodies which governed bicycle-racing were clearly unimpressed with the new technology because gearing systems were banned from competitive sport until well into the 1930s. It was perhaps as a result of their lack of interest that it was not until after the Second World War that the production of gear-change mechanisms developed beyond a small-scale artisan industry.

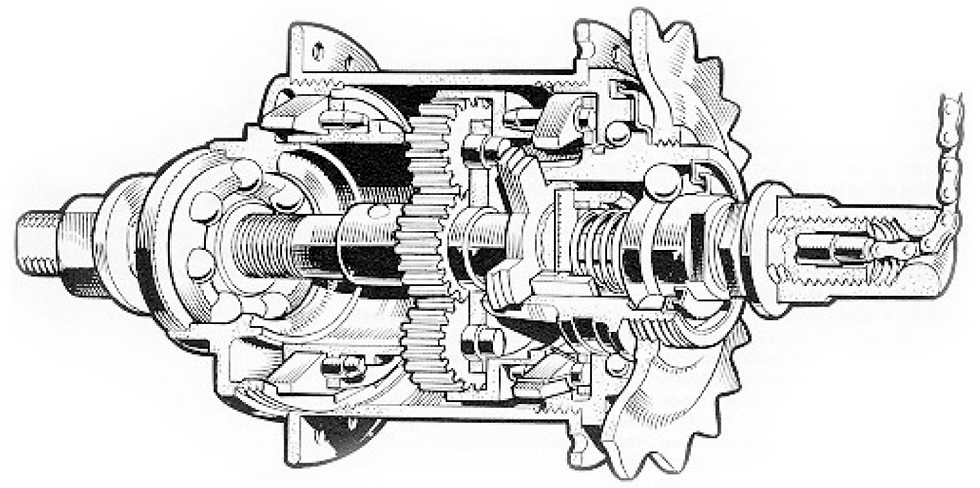

The boom in post-war European manufacturing combined with the need for low-cost transport and, at last, official approval for the use of variable gearing in bicycle sport saw the niche industry develop on a larger scale and become concentrated into fewer hands. In Britain the pre-war collaboration between James Bowder, owner of the vast Raleigh bicycle business and engineers Henry Sturmer and James Archer bore post-war fruit with their revolutionary 3-speed gearbox. Made in Nottingham, the Sturmey-Archer mechanism was securely sealed from dirt and grit within the rear-wheel hub. The tiny, hidden-from-view ‘epicyclic’ mechanism can be visualised as tiny gearwheels running around those in the centre, perhaps better imagined by the alternative label of ‘planetary’.

Image 2: The revolutionary three-speed gearbox

In modern times this form of gearing has been taken to a higher level by the sophisticated - and expensive - Rohloff hub-mounted transmission, which manages to incorporate 14 speeds in its compact aluminium casing. Still controlled by Bernard and Barbara Rohloff in a small factory in central Germany, the company’s products are appreciated by a niche global following.

In contrast to these out-of-sight hub-gears, the derailleur mechanism is highly visible. It was advanced most notably by Campagnolo of Vincenza, Italy, not only by offering an ever-wider range of speeds, but through their typically Italian design skills they reduced its weight to make it the choice of sporting and racing cyclists. The demands of competition drove more recent technical developments as well as the consolidation of manufacturing into ever-fewer hands. In the 1980s Shimano of Japan packaged its systems to provide all of their own components which, perhaps deliberately, weren’t designed to work with any other manufacturer’s technology. The demand for arrow-straight racing in a tightly packed peleton was discovered to be incompatible with moving the hands to the traditional gear-shifting lever around knee-level. This led to gear-shifting being incorporated into the handlebars and, more recently, to instantaneous electronic shifting powered by a lightweight rechargeable battery.

Bicycle brakes remained much the same from the invention of metal wheels shod with pneumatic tyres; a pair of hard rubber ‘shoes’ clamping onto the rim of the wheel. It was the MTB’s introduction of mud to the equation which led to the development of disc brakes, which have gradually made their way into road-bike applications.

Weight has always been an issue in transport and never more so than when the power available only amounts, at best, to one tenth of a horsepower. The original ‘safety’ bike’s bulk has today been halved to around 9 kg (20 lbs) for road bikes and perhaps 2 kilos more for the rugged MTB. There is an ongoing debate between enthusiasts for the traditional steel frame and those who favour the newer carbon fibre which produces a frame around 0.5 Kg lighter, but it largely seems a matter of choice. From the point of view of longevity, the traditional steel frame perhaps has the lead, while it also appears to have greater capacity for eventual recycling.

In Part Three The Eco-Worrier will focus on the e-bike!

Comments